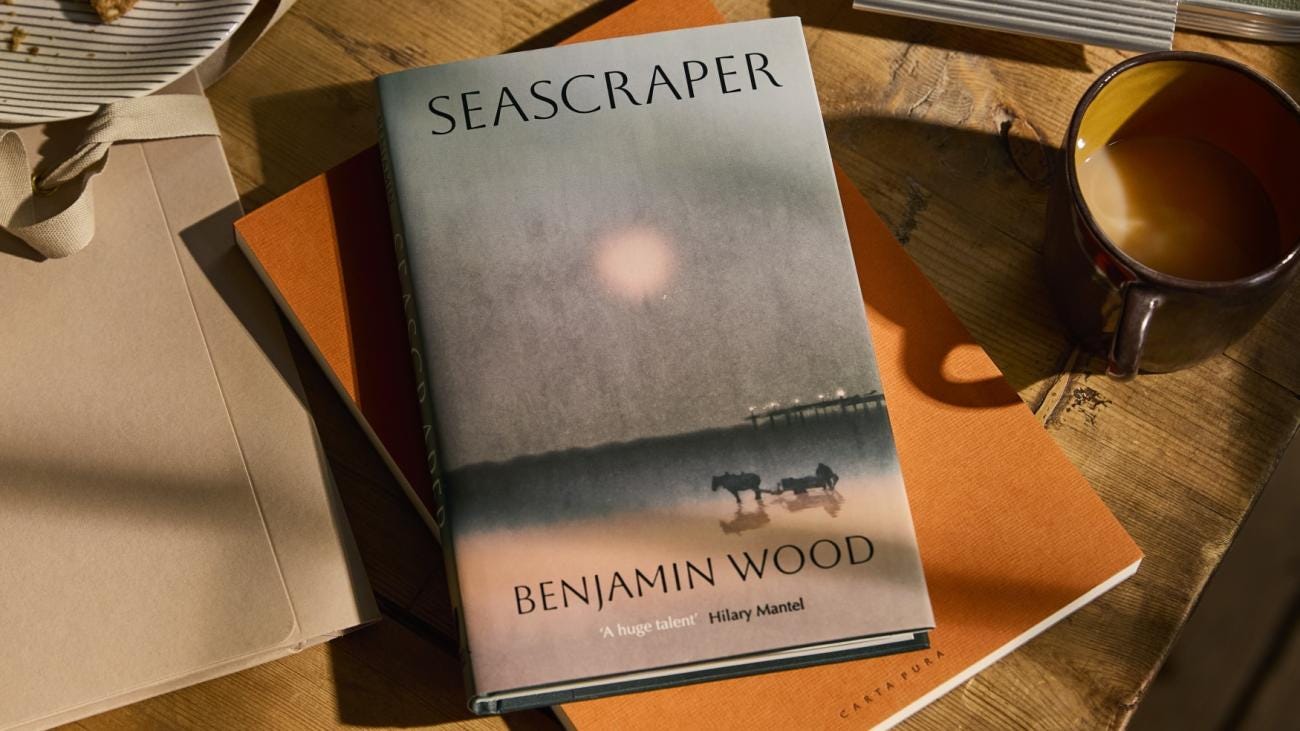

Seascraper by Benjamin Wood Review: A Beautiful Drift in Shallow Waters

The prose is attractive, but there are sink-holes in the plot.

Lord, it’s a hard life, son, I know that it is,

to rise with the tide in the morning at Longferry

Let me go home with the whiskets full of shrimp

Bury me here in these waters so I can be

a seascraper

Booker Prize Longlist, 2025

My rating: ⭐⭐⭐

Seascraper was an enjoyable, but short, read. I must confess, knowing nothing about this novel before reading, I thought it would be about a skyscraper on the sea. Hence my dismay (short-lived) when it was not a sci-fi epic about floating towns, but about a young man who scrapes the beach for shrimp.

Shrimp. Shrimp? A whole novel about shrimp? Luckily, the writing holds up. I felt totally immersed in the beautiful world of Longferry.

However, the original excitement died out for me, as the plot was hard to follow and the ending feeling unsatisfactory.

Summary

Seascraper follows Thomas Flett, a twenty-something “shanker” who earns a meagre living dragging for shrimp on the grey tidal flats of Longferry, a fictional coastal town in northern England. He lives a quiet, repetitive existence with his mother, pining for his neighbour Joan and nursing a secret dream of becoming a folk musician.

When a charismatic American named Edgar Acheson arrives claiming to be a Hollywood director scouting locations for a film, Thomas is drawn into his orbit, daring to imagine a different future for himself. But Edgar isn’t who he says he is, and after a harrowing night on the treacherous beach, the stranger’s true circumstances are revealed.

The Beautiful Drift: What This Book Does Well

I was allured by Wood’s prose, which has this mythical quality to it. The author’s vocabulary is expansive without being pretentious and Longferry has lore despite being entirely fictional. The protagonist’s mother, Lillian, is a real highlight of the novel: acerbic wit and a sardonic personality.

The writing feels lived-in and the similes and metaphors, often maritime, are earned:

There’s a haze of bacon grease inside the kitchen when he steps back in. His ma stands at the stove, barefooted in a dressing gown that seems to shrink a little every time she washes it. There’s only half an inch of height between them and just under sixteen years. She’s moving like a crab between the gas hob and the breadboard on the worktop, where two slabs of a loaf are lying thinly margarined.

The descriptions of quotidian life, of shanking for shrimp, of the fictional Hollywood world that Edgar Acheson inhabits, are all beautiful. As is the folk music undercurrent, which Wood has leaned into, releasing a recorded version of the titular song Thomas hears in his feverish dream. (link). This book is at its best when it focuses on the simplicity of Thomas’ existence, his desires for more and the complexity of his interpersonal relationships.

I also enjoyed the dream sequence on pp. 98 - 114, which adds elements of magical realism to an already dreamlike novel. Thomas almost drowns on the beach, meets his father in a dream and learns a heavenly sounding folk song. I think the way this book handles mortality, existence and fate is truly quite remarkable.1

All That Shimmers Isn’t Shrimp: Where it Goes Wrong

Now let me address the elephant in the room, or the shrimp in the basket: the plot. The ending, which if you haven’t read, stop reading here, is a pretty damp squib.

Edgar is revealed to be a fake and a Benzedrine addict. His mother shows him up and drags him away. Thomas is left to drive Edgar’s car down to Hertfordshire with his friend Harry Wyeth for money. It all happens quite abruptly. Thomas seems to take the news quite well. He plays the guitar for Joan, who he has affection for.

That’s about it.

After all the world-building at the start, the mania of the death-dream and the hope, life just goes on as it could have, or would have, had Edgar never appeared. The detail level of the first fifty pages is let down by the pacing in the last twenty. If this is a stylistic choice by the author, to show how everything changes after Thomas’ near-death-experience, I do not think it works.

I would also question Thomas’ characterisation. He is described as being and looking older than his young age:

He’s barely twenty years of age, but he goes shuffling down the hallway in his stocking feet with all the spryness of a care-home resident.

However, he does the work (and almost dies) for Edgar with limited critical thinking involved. Nothing in the text makes me feel, as a reader, that he is naïve; if anything he is quite self-aware. Except when he is with Edgar.

I wonder whether Wood is trying to make a point about celebrity culture. Perhaps he is trying to show the illusion of fame and how besotted people become with celebrities. Perhaps, because Thomas grows up without a father, he has a blind spot towards someone who could be a ‘father-figure’. Either way, Wood does not make this point well.

Conclusion

In all, I truly enjoyed the prose in this novel. It was refreshing, captivating and made me want to read more. Unfortunately, I wasn’t so keen on the plot. It did feel slightly unfinished in ways; the small size of the novella belying its true potential.

Have you read Seascraper? I’d love to hear your thoughts—especially if you disagree with me. Drop a comment below or find me on Goodreads.

Christopher Shimpton for the Times Literary Supplement calls this a ‘slight slightly silly dream sequence, in which Thomas writes a song with the father he never knew… prone to corniness”. Worth checking this out for a different point of view.